Introduction: Breaking Out of Wage and Price Stagnation

Japan has experienced a prolonged period of deflation, during which wages and prices stagnated for nearly three decades. Although there are recent signs of progress toward overcoming deflation, wage growth has not kept pace with rising prices. As a result, concerns about the future and the lack of real wage growth have dampened consumer spending. With purchasing power yet to recover sufficiently, there has been no meaningful improvement in the standard of living. Sustained wage growth is a key pillar for achieving stable economic growth.

In this article, I argue that investments in human capital are foundational for achieving sustainable wage growth. While the recent trend toward higher wages is a welcome development, an examination of the reasons behind the wage hikes raises questions about their long-term viability.

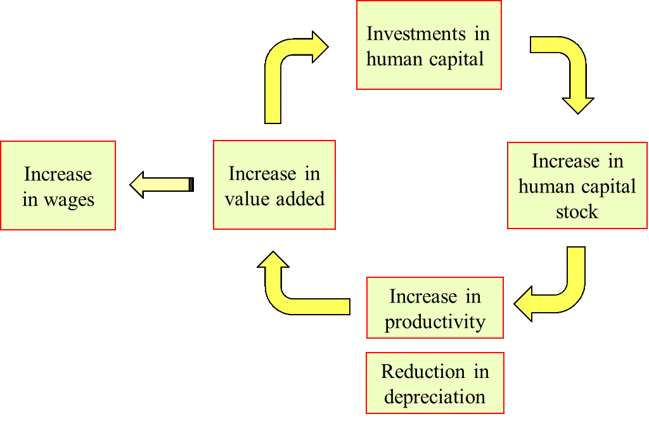

Wage increases are not a means to enhance productivity; rather, they are the result of improvements in productivity and added value. This virtuous cycle is driven by investments in human capital.

Hiroshi Ono

Hitotsubashi University Business School

* NOTE: This is a short summary of a chapter out of my book, which was later published in an article, both published in Japanese.

Ono, H. 2024. Human Capital and the Economic Approach to Human Behavior. Nihon Keizai Shimbun Shuppansha (In Japanese)

Ono, H. 2024. “Sustainable Wage Growth and the Role of Human Capital Investments.” Securities Analysts Journal 62: 35-45 [Special issue on “Corporate Behavior in Post-deflationary Japanese Economy”] (In Japanese).

Sustainable Wage Growth Requires Human Capital Investments

Productivity, defined here as the value added per labor hour, hinges on the accumulation of the stock of human capital—a blend of skills, knowledge, and experience. Human capital is the greatest asset that the company has. Like physical capital, human capital can depreciate. Avoiding the deterioration of skills requires continuous maintenance and investments through education and training.

The figure below illustrates the model of sustainable wage growth. The key points here are that investments in human capital are the engine for sustainable growth, and that wage increases are an outcome of productivity gains.

Why Companies Raised Wages: Survey Results from 2024

Japan saw a notable average wage increase of 5.1% in 2024—the highest in 33 years. But is this trend sustainable? According to a survey of 590 HR managers that I administered with HR vision in March 2024 (published in the 2024 Human Resources White Paper), 76% of companies raised wages between April 2023 and March 2024. While this is welcoming news, most companies that raised wages last year were not responding to strong business performance. Instead, they were trying to boost employee motivation, counter inflation, or keep up with competitors. Just one in three companies said the decision was based on improved productivity or profitability.

These results are troubling because the direction of wage increases and productivity is backwards: companies are increasing wages as a means to boost productivity, not as a result of productivity gains. It is not sustainable because wage hikes will only squeeze profits unless accompanied by productivity gains.

Interestingly, the survey also revealed that larger firms tend to raise wages due to external pressures. For example, large firms felt forced to do so in response to government pressures, or because of industry-wide norms, i.e. because “others firms are doing so.” Statistical correlations show that bigger companies’ wage decisions are less tied to performance and more to peer conformity or public expectations. This “obligatory” wage hike weakens the motivational impact of what economists call the “gift exchange” effect.

Gift Exchange Theory: Can Higher Wages Motivate Employees?

“Gift exchange” theory (Akerlof 1999) posits that when companies voluntarily offer higher wages, workers reciprocate with higher motivation and loyalty.[i] Yet this logic falters if employees perceive raises as a forced or token gesture. For example, a 2024 survey by Nomura Research Institute found that only 54% of employees who received a raise felt more motivated as a result. In other words, employers may raise wages as a gift expecting higher motivation, but only half of the employees are getting the message.

Furthermore, while pay increases may slightly improve morale or reduce shirking, its net benefits are unclear because it also incurs higher costs (e.g. Bewley, 1999; Cappelli & Chauvin, 1991).[ii] Intrinsic motivation or non-monetary incentives—such as meaningful work, recognition, psychological safety and job autonomy—play an equally important role in improving motivation and productivity (Ono 2019).[iii]

The Lost 30 Years: A Legacy of Underinvestment in Human Capital

After the early 1990s asset bubble burst, Japan entered a deflationary spiral. With prices flat or falling, companies struggled to raise revenues. Fear of losing market share in price-sensitive markets prevented companies from raising prices. Profits stalled. As a result, companies froze wages, curtailed hiring, and slashed investments in training—viewing people as costs to be minimized, not assets to be nurtured.

During the boom, firms over-hired. But after the bubble burst, instead of downsizing, most firms simply slowed hiring and avoided layoffs, owing to the inherent rigidity of the Japanese labor market, and the protectionist constraints of stakeholder capitalism. The unemployment rate rose only modestly, peaking at 5.5% in 2002—a sign not necessarily of resilience but of sluggish employment adjustment.

This low labor market fluidity hampered innovation and productivity. As wages remained flat, so did investment in human capital. According to Miyagawa et al (2020), human capital investments in Japan peaked in 1991 and declined sharply thereafter.[iv] From 1995 to 2018, Japan’s estimated human capital stock fell from 11 trillion yen to below 4 trillion yen (Miyagawa et al 2015).[v]

A particularly alarming trend is the expansion of nonstandard employment. As firms avoided hiring regular workers, they increased reliance on temporary or part-time labor. These workers are hired on an as-needed basis. They are excluded from career development tracks. Companies do not invest in them, so they contribute little to the human capital base. By 2020, nonstandard workers made up 37.1% of the workforce, up from 15.3% in 1984.

The lost 30 years thus resulted in a significant erosion of Japan’s human capital base. It was a self-reinforcing cycle where low growth led to low investment in people, which in turn perpetuated low growth. During this time, Japan dropped from number one in IMD’s World Competitiveness Rankings (in 1989) to number 35 in 2023.

Wage Growth Today: Welcome But Not Sustainable

Even as deflation appears to be ending—with Japan recording over 2% annual inflation since 2022—real wage growth remains uneven and fragile. The post-2023 wage hikes, though welcome, risk repeating past mistakes if not accompanied by robust investments in human capital.

Wage increases spurred by social pressure, political expectation, or external benchmarking—as seen among large firms—may offer short-term relief but lack the foundation for long-term value creation. If employees perceive these raises as routine or unearned, they may fall short of driving productivity growth.

Moreover, economic theory predicts that marginal utility of income diminishes: low-income workers may realize real improvements from a 5% raise, but the same increase may barely register for higher-income employees. This undermines the use of across-the-board wage hikes as a motivational tool. Over time, maintaining morale will require ever-greater pay increases—a strategy that is neither efficient nor sustainable.

Towards a New Model of Stakeholder Capitalism: More Investments, Less Protection

Japan has long prided itself on stakeholder capitalism, where firms prioritize employee welfare. But ironically, this well-intentioned protectionism has at the same time stifled growth by discouraging investments in human capital. What is required now is a shift from a defensive to a more proactive stakeholder engagement, from protecting employees to investing in them.

To regain international competitiveness and to break free from deflationary inertia, Japan must embrace proactive, strategic human capital investments, through such measures as renewed investments in employee training, shift towards performance-based compensation, and more flexible labor market policies to promote talent mobility.

Ultimately, sustainable wage growth is an outcome of productivity gains and value creation. The goal is not merely to raise wages—but to build a system where people, companies, and society all flourish together. Human capital investments are the foundation of economic growth, and the path forward for Japan’s stakeholder capitalism.

[i] Akerlof, G. A. 1982. “Labor Contracts as Partial Gift Exchange” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 97: 543–569.

[ii] Bewley, T. F.. 1999. Why Wages Don’t Fall during a Recession. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Cappelli, P. and K. Chauvin. 1991. “An Interplant Test of the Efficiency Wage Hypothesis.” The

Quarterly Journal of Economics 106: 769-787.

[iii] Ono, Hiroshi. 2019. “Conditions for Improving the Quality of Work – Lessons from Case Studies.” Japanese Journal of Labour Studies 706: 28-41 (In Japanese).

[iv] Miyagawa, T. M. Takizawa and D. Miyakawa. 2020. “Human capital investments and productivity” (In Japanese). In White Paper on Productivity. Japan Productivity Center.

[v] Miyagawa, T. et al. 2015. “The Role of Intangible Investment on Economic Growth in Japan” (In Japanese). RIETI Policy Discussion Paper Series 15-P-010.